I thought you hated it when I played

On a recent family holiday, my wife and I signed up for a free salsa lesson by the side of Melbourne street. Our kids watched on, bored. But I was having a ball. I can’t really dance. And I’m terrified of dancing in public. But here I was, dancing on a city street, surrounded by strangers. And most of them were just as bad as me. All of us tripping over our own feet.

“Matt, you have so much potential.

But with you, it’s always one step forward and two steps back.”

He wasn’t talking about my dancing.

This was an awkward let’s-clear-the-air kind of conversation.

It didn’t really clear the air.

But more than 25 years later, his words still stick.

In part because there’s some truth to them.

I don’t know if you can relate to this.

But there’s often a gap between how I’d like to act and how I do act.

Between who I am and who I want to be.

And often, it’s not my abilities or intentions that let me down.

It’s my reactions to stress and relationship challenges that get in my way.

Too often, I lack confidence. I depend on people’s approval. I get defensive. I’m more sensitive than I would like to be. And less adaptable.

One step forward and two steps back. Tripping over my own feet.

There’s a kid in my son’s soccer team who is extremely hard on himself. Every time he makes the slightest mistake his face falls, his body slumps and he hits himself in the head. And the more he gets down on himself, the worse he plays.

I’ve tried talking him out of it. But his self-condemnation is so ingrained. It’s rooted somewhere logic can’t easily reach.

I asked his dad, and he explained:

“He gets it from his grandad. He’s the same.”

But that got me thinking.

- How does a kid catch self-criticism from his grandad?

- How do our families shape us?

- And how can this kid unlearn those family behaviours so he can get out of his own way?

One of Murray Bowen’s key contributions was to notice - and describe - the almost invisible ways our families shape us. He observed that families play a vital role as anxiety-managing machines.

Notice three things.

1. Families use a variety of mechanisms to manage anxiety and keep things as calm as possible. We’ll explore these more in future blog posts, but these mechanisms include things like:

- distancing

- conflict

- triangles

- over/under-functioning relationships

2. Whatever mechanisms a family uses shape how members of that family deal with relational challenges in all other spheres of life.

3. Bowen theory provides a lens to help us notice and understand the instinctive behaviours we learned in our families. This gives us a chance to be more thoughtful so we can choose different ways of responding and get out of our own way.

Ted Lasso provides a great illustration of how this works. It’s basically a story about a bunch of people who keep getting in their own way but who learn over time to manage their instinctive behaviours and show up more often as the people they want to be.

So let’s look at an example.

Out of all the characters in Ted Lasso, there’s one who gets in his own way more than anyone else. His name is Nate Shelley.

Nate has a brilliant mind. And his career progression is stratospheric. Within three seasons of Ted Lasso, he goes from the very bottom of the football food chain, as the“kit man” at AFC Richmond, to the very top, as head coach at West Ham FC.

And yet he’s still the same old Nate. He:

- Tiptoes around everyone else’s feelings.

- Fears disapproval like parents fear treading on left-out Lego in the dead of night.

- Tries to avoid conflict like we used to try to avoid catching covid.

- Sucks in his opinions like a middle-aged man sucks in his gut in front of a mirror.

- Enters every room wishing he was invisible while at the same time desperately hoping someone will see him and approve of him.

- Shifts his shape constantly in a desperate attempt to please.

Nate is a strategic genius. Yet when it comes to his relationships - with his parents, girlfriend, peers, bosses, and even random strangers - he’s like an awkward teenager learning to dance and tripping over his feet.

With Nate, it’s always one step forward and two steps back.

So how did Nate’s family shape him?

Meet Nate’s parents. Lloyd and Maria Shelley. In Season 2, they celebrate their 35th wedding anniversary. And Nate is desperate to impress his dad, so he organises a special dinner at his dad’s favourite restaurant to mark the occasion.

But from the moment Lloyd arrives, he criticises and complains. As Nate bumbles up to the waitress to confirm their booking, Lloyd interrupts:

“Stop blabbing up the young lady. Your mother's hungry.

But Maria jumps in to protect her son:

Stop it, Lloyd. Forgive your father, my darling.

Nothing Nate does is ever good enough for Lloyd - no wonder Nate is so desperate to please. And so, we might assume that Lloyd is the cause of Nate’s crippled confidence.

But what if it’s not as simple as that?

So - if we want to understand what drives our instinctive behaviours, we need a different perspective. We can’t just get sucked into blaming this person or that person. We need to try to see the role that each person plays.

Murray Bowen says it’s a bit like watching a game of sport. When you’re down on the sidelines, you feel the intensity, but that’s not always the best place to see what’s going on. He observes:

“The view from the top of the stadium makes it possible to see broad patterns of movement and team functioning that are obscured by the close-up view.”

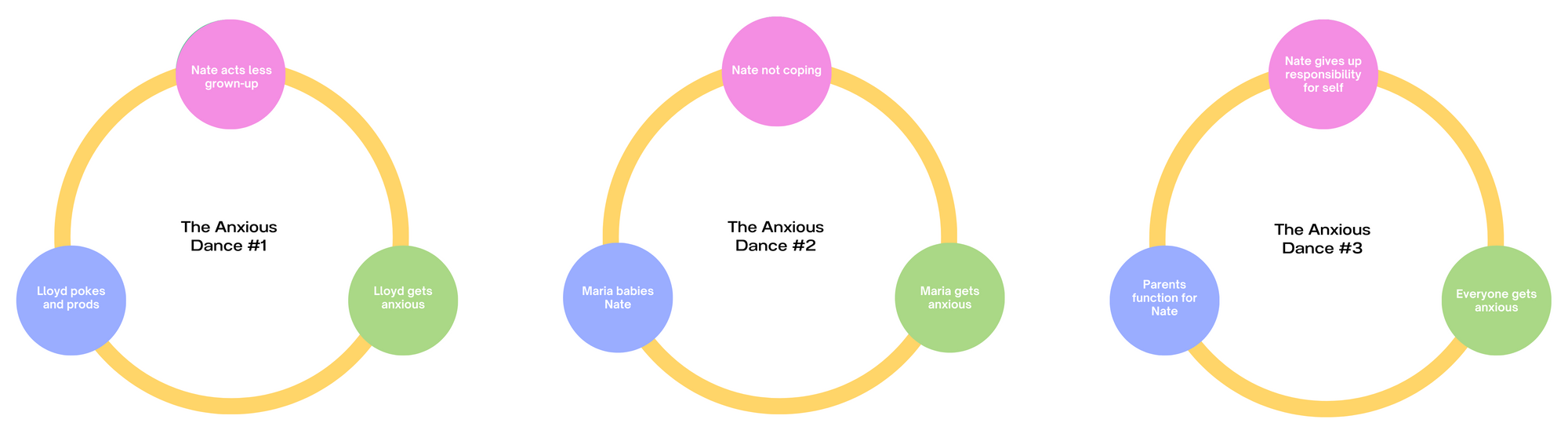

So what do we notice when we zoom out from Lloyd's criticism and observe how Lloyd, Maria and Nate interact as they manage their anxiety?

- Maria and Lloyd are distanced.

Maria and Lloyd each object to the way the other one parents Nate. Lloyd shoots disapproving looks at Maria when he thinks she's coddling Nate. Maria shushes Lloyd when she thinks he’s too critical.

2. Maria and Lloyd both function for Nate.

Close up, Maria and Lloyd seem very different. Her care contrasts with his complaints. But zoomed-out, we see there's something similar in how they parent. They both keep jumping in to function for Nate. Lloyd tries to give him direction. Maria tries to give him support. But both act as if Nate isn’t capable of functioning for himself.

3. Nate reacts to his parents’ attention by becoming more sensitive to them and less “solid” in himself.

i. More SENSITIVE to them

The more Nate’s parents intrude in his life, the more sensitive he becomes to their intrusions. In the same way that my guitar tuner picks up on the slightest changes in frequency in my strings, so I can make the necessary adjustments and bring them back into tune, Nate becomes more and more sensitive to the discord in his family, so he can make the necessary adjustments to his behaviour and restore harmony in the family.

- To calm Lloyd down, Nate tries to please him.

- To calm Maria down, Nate lets her coddle him.

- Because if he calms them down, then he feels calmer too.

ii. Less SPACE for self

The more Nate’s parents function for him, the less space he has to think and act for himself. The more he follows their lead, the less he takes responsibility. It’s hard to work out who he is or what he stands for when they act on his behalf.

4. This dance calms the family down. Until it doesn’t.

They each act instinctively to calm the family down. But the more they get stuck in these patterns of behaviour the more anxious they get.

- So both parents keep functioning for Nate.

- Nate keeps giving up self.

- Everyone keeps getting more anxious.

- And the anxious dance continues.

Until Season 3.

When Nate resigns from his dream job at West Ham, he falls into a funk. He sneaks back to his parents’ home and hunkers down in his childhood bedroom, refusing to come out. Of course, you can guess how his parents respond! Lloyd disapproves. Maria coddles. She leaves an endless supply of meals outside Nate's bedroom door. Nate under-functions. He leaves an endless supply of dirty dishes for her to collect.

It’s the same old dance!

But then, when he thinks his parents are out, Nate picks up his old violin and plays. Beautifully. He’s so immersed in the music he doesn’t realise his dad has entered the room.

Nate: Oh, sorry... sorry if I disturbed you ( stammers )

Lloyd: No, no, not at all. I really miss hearing you play.

That seems like a new dance step. It's an 'I statement' instead of a 'you' statement.

Nate: You do?

Lloyd: Of course.

Nate: I thought you hated it when I played.

Another new step. Nate gets curious.

Lloyd: Why on earth would you think that?

Nate: ’Cause you literally said that to me once, Dad. You said I didn’t practice enough. How I was squandering my potential and wasting my privilege.

And another step. Nate is direct instead of ducking and weaving a difficult conversation.

Lloyd: You were given opportunities I never had, and so I expected a lot from you…I’m sorry. I didn't know how to parent a genius.

And another new step. An apology. Vulnerability.

Nate: What?

Lloyd: A genius. You're brilliant, son... But you're right. I pushed you to be the best at everything, even at violin. 'Cause I thought that's what I had to do.

Nate: I just... I just liked playing.

Lloyd: Nathan, be successful, don't be successful. I never cared about any of that. I just want my son to be happy.

I’m not crying. You’re crying.

- Notice what happens when Lloyd stands back and listens and just enjoys his son instead of imposing his expectations?

When Lloyd gives Nate a bit more space, it changes the dance. Now Nate has a bit more room to be his own person. He’s able to more honest with his dad. His dad is able to be more open. In a sense, there’s more emotional space or separation between them - they give each other more room to be authentic - yet this increased separation fosters a new and deeper connection.

And everything seems a bit less anxious.

At least for now.

Maybe we can start with small changes. I've adopted a little motto to help me be a bit more thoughtful and to give others a bit more space; "presence not pressure".

It's nothing too radical.

I'm just aiming for one step forward and one step back.

Like me learning to salsa.

So what has this got you thinking about?

- When and how do you get in your own way? In what ways do you instinctively react to tension or pressure?

- What does the dance in your family look like when things get anxious?

- Which mechanisms do you tend to use to calm things down in your family: distance? conflict? triangles? over-functioning or under-functioning? And where do you notice yourself using these same mechanisms in other parts of life?

- Think of one challenging relationship where you often fall into this pattern of behaviour without thinking. What is one thing you could do differently to try a new dance step? What would it look like in that relationship for you to be a more mature self?

A final thought: It turns out Lloyd does love his son. Perhaps just as much as Maria does. But, in a twisted yet completely normal way, his "love" generated the anxious concern which fuelled his criticism. Just as her "love" generated the concern which drove her to treat Nate like a little child. This is why parenting is about more than “love”. That’s a topic for a future blog post!

And speaking of future blog posts, stay tuned for a big changeroom announcement!